In the next instalment of his reflections on deacon of the month, Jonathan Halliwell examines the legacy of Nicholas Ferrar, considering how he inhabited the qualities required of a deacon today.

Nicholas Ferrar and the Little Gidding Community

‘Born in London in 1592, Nicholas Ferrar was educated at Clare Hall Cambridge and elected a Fellow there in 1610. From 1613, he travelled extensively on the continent for five years, trying his hand as a businessman and then as a parliamentarian on his return. In 1625, he moved to Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire, then a derelict manor-house with a chapel which was being used as a hay barn. He was joined by his brother and sister and their families and by his mother, and they established together a community life of prayer, using The Book of Common Prayer, and a life of charitable works in the locality. He was ordained to the diaconate by William Laud the year after they arrived. He wrote to his niece in 1631, “I purpose and hope by God’s grace to be to you not as a master but as a partner and fellow student.” This indicates the depth and feeling of the community life Nicholas and his family strove to maintain. After the death of Nicholas on 2 December 1637, the community was broken up in 1646 by the Puritans, who were suspicious of it and referred to it as the Arminian Nunnery. They feared it promoting the return of Romish practices into England, and so all Nicholas’s manuscripts were burned.’ (Exciting Holiness)

The deacon as community builder

Nicholas Ferrar’s legacy for the deacon’s calling as community educator was rooted in a rule of life comprising prayer, study and service. Little Gidding was intended to be a spiritual, intellectual and service community. This outreach to the community arose through his work as a physician providing medical care in the neighbourhood. This was one of the ways in which he fostered networks of spiritual friendship.

Within his own family, he established a model for the community in which every member had a part to play. During the week, the family processed to the church for services of Matins, the Litany, and Evensong, which were led by Nicholas. On Sundays, the local children came to Matins and afterwards recited the psalms they had learned, receiving a penny for each correctly memorised. Once a month, the vicar of Great Gidding celebrated Holy Communion.

Little Gidding Church – The website of St John’s Church, Little Gidding, Cambridgeshire, England

The deacon’s responsibility for the gospel

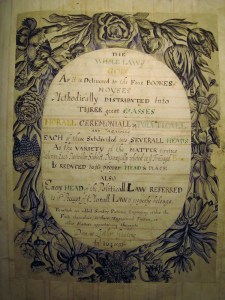

One of the ways in which the house mirrored the efforts of the Reformed church was in fostering a shared responsibility for prayer and preaching through the creation of an integrated gospel book. This “harmony” of all four gospels provided the narrative for the hourly gospel readings. The printed books became known as the Little Gidding Harmonies. To create them, individual lines were cut from the four gospel narratives and pasted together on the page to make one continuous text. The pages were also illustrated with engravings, some of which Nicholas may have brought back from his continental travels many years earlier. This creative project was used to instruct the younger members of the extended family in the gospel story and to develop their manual dexterity. It reminds us of the deacon’s responsibility for teaching (catechesis) and proclaiming the gospel. But this was achieved through mutual flourishing, since it was the women of the family who took responsibility for the manual labour of the books.

MS 262: The Little Gidding Harmonies – St John’s College Library, Oxford

The deacon of the church

This bring me to the third aspect of Ferrar’s legacy, prayerfulness; at the heart of a deacon’s calling is to love and serve Christ. This was a community saturated in prayer. We have touched already on how he established a regular round of prayer based on Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. But in Advent, 1632, he took this one step further. At the suggestion of his friend and contemporary from Cambridge, George Herbert, Ferrar added an extra watch from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. to prepare for the Second Coming, encouraging family members to take it in turns to recite the psalms together. At 1 a.m. Ferrar himself arose and took watch, often continuing the watch by himself. He chose to do the watch several times a week even though the rule required each household member to do so only once a week. In the autumn of 1637 Nicholas sickened, dying on the day after Advent Sunday at 1 am, the hour at which he had always risen to begin his prayers. [Source: Timothy Fuller, ‘Anglican Saint, Anglican Poet: Nicholas Ferrar and T. S. Eliot at Little Gidding’, Pro Ecclesia Vol. XXVI, No. 4: 435-449.]

In our own times, when the survival of the parish church is under threat, Little Gidding is a timely reminder of the enduring value of church buildings, which acquire their spiritual depth over time, their sense of otherness, by being hallowed in prayer. In some cases, they become centres of pilgrimage. A pilgrimage to Little Gidding, whether physical or spiritual, draws strength from T.S. Eliot’s observation of constancy in prayer and advice to the pilgrim: ‘You are here to kneel in a place where prayer has been valid’:

If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

And what the dead had no speech for, when living,

They can tell you, being dead: the communication

Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

Here, the intersection of the timeless moment

Is England and nowhere. Never and always.

(T.S.Eliot, Four Quartets, IV Little Gidding)

But let us close with Nicholas Ferrar’s joyful prayer of thanksgiving:

‘Thou hast given us a freedom from all other affairs that we may without distraction attend Thy service. That Holy Gospel which came down from heaven, with things the angels desire to look into, is by Thy goodness continually open to our view; the sweet music thereof is continually sounding in our ears; heavenly songs are by thy mercy put into our mouths, and our tongues and lips are made daily instruments of pouring forth Thy praise. This, Lord, is the work of, and this the pleasure of, angels in heaven; and dost Thou vouchsafe to make us partakers of so high a happiness? Thy knowledge of Thee and of Thy Son is everlasting life. Thus service is perfect freedom; how happy are we that thou dost constantly retain us in the daily exercises thereof!’

(from the Storybooks of Little Gidding; Margaret Cropper Flame Touches Flame, London 1949, pp.64-66)